- 'Afghan-led, Afghan-owned' is way f...

- China's top internet regulator mull...

- China's specific security review on...

- Wooing Bangladesh to Quad against C...

- ‘Cheaper costs than China’ not adeq...

- Iran Nuclear Issue: Dual-Track Wisd...

- China-Sri Lanka Cooperation during ...

- India slinging dirt on China with c...

- New Delhi’s moves with Hanoi on S. ...

- Chinese initiative calls for peace,...

- Identifying and Addressing Major Is...

- China's Relations with Two Sudans: ...

- Perspectives on the Future of China...

- A Promising Partnership between BRI...

- The Sudan - South Sudan Reconciliat...

- China's Relations with Two Sudans:F...

- China’s Role in Sudan and South Sud...

- The EU and the Sudans

- Development through Peace: Could Ch...

- China, Sudan and South Sudan Relati...

The Ramawi terror did not come out of the blue. It is a result of decades of economic polarization, political exclusion, neglect of terrorism by the Aquino administration, and ISIL’s collapse in Syria and Iraq. If the stabilization fails now, terror will spread beyond Mindanao. - This is the second commentary about the Philippines from an international viewpoint.

On May 23, 2017, the ongoing armed conflict started in Marawi, the capital of Lanao del Sur in Mindanao. Philippine government forces were surprised by affiliated militants of the Islamic State of Iraq and Levant (ISIL), including the Maute and Abu Sayyaf Salafi jihadists groups.

Initially, President Duterte declared a 2-month martial law in Mindanao hoping to suppress the terrorist insurgency immediately. In July, government extended martial law in Mindanao to the year-end. By August, after Duterte informed the leaders of the Senate and House about “new terror plots in Mindanao,” he asked for 30,000 more troops to crack down on ISIL and other emerging threats.

Despite some criticism, the simple fact is that, without Duterte’s decisive action and martial law, Jihadists would have gained a foothold in Mindanao and terror would already be spreading in the Philippines and regionally.

To the old entrenched interests, the Marawi story is inconvenient domestically and internationally.

Domestic neglect, international geopolitics

In March 2016, after years of gross neglect of emerging terrorist threats and the 2015 Mamasapano massacre, then-President Aquino stated that the Islamic State had no presence in the Philippines, despite ISIL’s recovered insignias and documents, a foothold, training and jihadist loyalists in the country. Moreover, the number of ISIL sympathizers had been on the rise since 2014; perhaps since US military interventions in the Middle East in the early 2000s.

Domestically, It was this neglect that led to the rise of the ISIL-led coalition under Isnilon Hapilon, who had fought in the Moro National Liberation Front and the Abu Sayyaf group, and the Maute brothers; scions of a political family clan, who used to head a private militia that engaged in extortion and pledged alliance to ISIL a year before President Aquino still denied its presence in the country.

It was this fatal neglect that allowed ISIL to infiltrate Mindanao, but also to escalate the regionalization of Jihadist terror. Today, the “East Asia Wilayah” comprises jihadists from several Southeast Asian nations (Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar), and potentially others from the Middle East, North Africa and Chinese Uyghurs. Indonesia alone has the largest Muslim population in the world and there are ISIL cells in most provinces.

International media has contributed to the neglect by “geopoliticizing” the roots of terror in Mindanao. Last June, New York Times released a story by Richard C. Paddock which claimed that “Duterte, focused on drug users in Philippines, ignored rise of ISIS.” In reality, Duterte has for years warned about the emerging terrorist threat in the country, even when others ignored such calls.

A month earlier Paddock had released another story, “Mysterious Blast in Philippines Fuels Rodrigo Duterte’s ‘Hatred’ of US,” in which he used amateur psychology to explain away the infamous Meiring case in Davao in the early 2000s. Reportedly, the latter case was a CIA effort to cooperate with Jihadists to foster destabilization through Mindanao in the Southeast Asia, which would then be used to legitimize greater US presence in the region (US collaboration with “moderate jihadists” in Syria in the 2010s suggests similar footprints).

But how did the impoverished Mindanao morph into a terror foothold?

Mindanao as Islamic State destination

When the Aquino administration opted for its pivot to the US, re-established old military ties with the Pentagon, and invited American troops back to Philippines, it – unintendedly and yet by design – virtually ensured that the Philippines would morph into a major target for jihadists.

In June 2012, months after the Obama administration’s pivot to Asia, the Khilafah, a major jihadist website, argued that since “the US will keep six aircraft carriers in the Asia-Pacific and will shift 60% of its warships to the region, over the coming years until 2020,” it obligated the Jihadists to bring Islamic power in the region.

When the ISIL began terror in Iraq and Syria in 2014, I warned that the first ISIL-affiliated attacks in world capitals and Asia were only a matter of time, no longer a matter of principle. Historical and geographic forces fueled the coming upsurge.

In March 2016, Wikileaks released a massive load of US diplomatic cables dating back to 1979. According to Julian Assange, the evidence indicated that the decision by the CIA and Saudi Arabia to plough billions of dollars into arming the Mujahideen fighters in Afghanistan against the Soviet Union paved the way to the creation of al-Qaeda and, eventually, to the ISIL. US counter-terrorist studies support the claim.

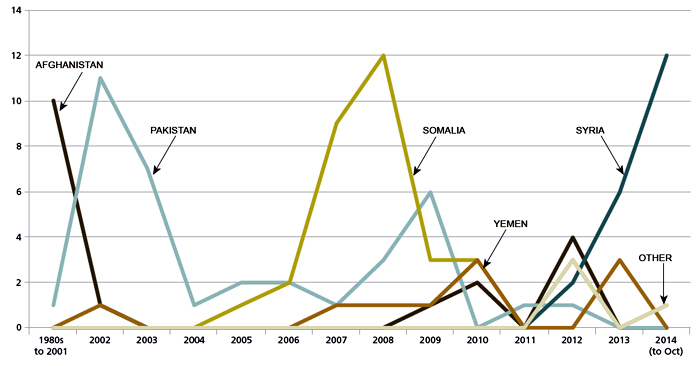

Historically, Jihadism originates from the Mujahedin – the guerrilla-type Islamist Afghan warriors in the Soviet–Afghan War – which Washington exploited in the 1980s. Yet, preferences for destinations have changed over time. Until 2001, Afghanistan, where volunteers went to join al Qaeda or the Taliban (or the Mujahedin in the 1980s), was the key destination. After US overthrow of the Taliban government, Pakistan became the preferred destination. Events in Somalia made it the preferred destination in 2007-8, while the civil war in Syria began to attract foreign fighters, with the number increasing in 2013-14 (Figure 1).

In each case, US interventions paved the way to massive destabilization, which in turn supported the spread of terror. Nevertheless, the footholds of devastation – Afghanistan, Pakistan, Somalia, and Yemen – that preceded the ISIL were largely regional and had few spillovers internationally.

Iraq and Syria changed the old status quo. Now Middle East battlefields became sites of international interventions, which had worldwide consequences and frequent spillovers, especially when the fighters would return home; often with battle-weary resentment but knowledge about fire-arms, explosives and insurgency.

Figure 1 Intended Destinations of Would-Be Jihadists Over Time

Source: RAND, 2014

At the same time, the role of Asia and the Philippines have become central to the Jihadi world. The most recent issue of Rumiyah, the ISIL online magazine used for propaganda and recruitment, features a cover story about “The Jihad in East Asia” (in Caliphate parlance that connotes Southeast, South and East Asia). Typically, it portrays the Marawi fight as a struggle between good (ISIL) and evil (“Filipino crusaders”), which derives from decade-old efforts of the Abu Sayyaf Islamic movement “to open a jihad front there.”

Clearly, the strategic objective of the Rumiyah is to recruit new cadres of militants to launch multiple terror fronts in Asia. But why have the ISIL and its precursors pushed Mindanao as the key destination?

Mindanao’s economic suffering

Geographically, Mindanao is often seen as the Philippines’ “food basket.” Historically, it has witnessed colonial violence by Spain, America and Japan; several communist insurgencies; armed Moro separatist movements, and now terrorist attacks.

Along with Palawan, the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (ARMM) is the only area in the Philippines with significant Muslim presence. In 2012, the struggle for greater autonomy in the ARMM deteriorated with President Aquino’s failure to establish the Bangsamoro.

ARMM is a distinct territory, with its own culture and identity and has served as home to Muslim Filipinos since the 15th century. The Moros share a 400 year resistance of Bangsamoro (Moro nation) against Spanish, American, and Japanese rule. Historians remind us that the US surveillance state and torture, including waterboarding, was first used in Mindanao more than a century ago.

According a decade-old US intelligence assessment, the Mindanao may have “untapped minerals worth between $840 billion to $1 trillion,” which explains the great domestic and foreign interest in the region. Yet, today the ARRM remains one of the most impoverished areas in the country.

Income polarization is alarming. While real per capita income in Philippine capital region is almost three times the national average, it is 17 times higher than average per capita income in the ARMM. In international comparison, metro Manila’s capita incomes are about the same as the average in Mexico, Brazil or China. But in Muslim Mindanao, per capita incomes are more comparable with those in Mozambique and Congo. Among Jihadist locations, ARMM is behind Syria, Pakistan and Yemen but at par with Afghanistan – which makes it an ideal target (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Per Capita Incomes in International Comparison, 2016

Sources: IMF, World Bank, CIA

Despite their struggle against economic, political and military odds, the majority of Muslims in Mindanao continue to have great hope in peace and the Duterte administration. Before the jihadist fighting, criminal and narcotic activities actually declined in the area. But now the future of Muslim Mindanao’s ailing and decent population is threatened.

Four steps toward progress

Due to legacies of insurgencies, ethnic and religious disparities and huge income polarization, Muslim Mindanao could serve as an ideal target for Jihadist footholds, training, recruitment, and propaganda. Such nightmare scenarios can be avoided, but only by decisive actions.

1. Restoring peace and stability in the near-term. In the short-term, Duterte administration’s effort to pacify terror in ARMM is vital, including the extension of the martial law. The threat must be neutralized now when it is still marginal, soft and fragmented and the majority of the ARMM supports government’s efforts to restore peace and stability in the region.

2. Acceleration of economic development across ARMM. In the medium-term, it is critical to escalate all viable efforts at economic development, through the stabilization of key cities and host regions, by prioritizing the Mindanao Development Corridors to intensify development.

3. Initiation of medium- and long-term regional integration. This is vital to ensure regional integration in parallel with other regional corridors. Stabilization is not possible without cooperation with neighboring countries that share similar threats, especially Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore, even Australia and Japan.

4. Cooperation with major Asian and Pacific powers. This is critical in economic development (foreign investment, trade, aid), China-led pan-regional globalization (OBOR) and regional counter-intelligence. The joint patrols in the Sulu Sea are a good start, but only a beginning. The long-term objective is predicated on greater collaboration with not just China and the US, but Russia, Japan and Australia, as well as Saudi Arabia and Iran – that is, nations that have a significant presence in Asia and that are central to stabilization in the Middle East.

True development requires peace and stabilization in Mindanao, while national integration in the Philippines supports regional integration in Southeast Asia. Major powers have a supportive role in conflict resolution, if they can offer support.

Failure is not an option because it would mean the spread of terror first into major Philippine cities, and then across Southeast Asia. (The Manila Times on August 7, 2017)

Source of documents:The Manila Times, August 7, 2017