- China’s Foreign Policy under Presid...

- The Contexts of and Roads towards t...

- Seeking for the International Relat...

- Three Features in China’s Diplomati...

- Smart gap widening

- Indian economy looks increasingly b...

- Reflecting on and Redefining of Mul...

- The Green Ladder & the Energy Leade...

- The Green Ladder & the Energy Leade...

- China-Sri Lanka Cooperation during ...

- The Establishment of the Informal M...

- China’s Economic Initiatives in th...

- Perspective from China’s Internatio...

- Commentary on The U. S. Arctic Coun...

- “Polar Silk Road”and China-Nordic C...

- Opportunities and Challenges of Joi...

- Opportunities and Challenges of Joi...

- Strategic Stability in Cyberspace: ...

- Promoting Peace Through Sustainable...

- Overview of the 2016 Chinese G20 Pr...

- Leading the Global Race to Zero Emi...

- Leading the Global Race to Zero Emi...

- Addressing the Vaccine Gap: Goal-ba...

- The Tragedy of Missed Opportunities

- Working Together with One Heart: P...

- China's growing engagement with the...

- Perspectives on the Global Economic...

- International Cooperation for the C...

- The EU and Huawei 5G technology aga...

- THE ASIAN RESEARCH NETWORK: SURVEY ...

Jan 01 0001

City and the Transformation of the International

By TANG Wei

The increasingly diversified series of actors that have entered into the international system in the post-Cold War era is the cause for examining the ongoing reorganization of the system. Joseph Stieglitz said that in the 21st century there are two prominent events: one is the hi-tech revolution in the U.S. and the other is urbanization in China. The hi-tech revolution led to the rise of informatization which further promotes globalization, while urbanization benefits from informatization and globalization, and the confluence of these forces have a significant effect on the global economy. Following this logic, some theorists posit that global order in the 21st century will not be dominated by nations such as America or China, sovereign unions such as G20, G2, or the UN, but will increasingly rely upon urban governance. Cities that possess a relatively large population, occupy some territory, and monopolize some resources, directly provide public goods to the residents and surrounding areas, thus turning themselves into the holder of structural power, namely “security, production, finance and knowledge” elaborated by Susan Strange. Today,as urbanization sees half of the world population entering into urban areas, cities as global actors increasingly require attention. Urban development, inter-city interaction, and the transformation of the international system have become tightly intertwined, thus the logic of cities and transformation of the international system necessitates exploration.

I. The Formation of a World City Network

The increasing decentralization of global resource allocation is a natural mechanism for integrating more cities into the circulatory system of the world economy. Jane Jacobs links dynamic cities to economic development, in which cities come together in groups that need each other to prosper.[①] Increasingly fierce competition on the global market compels cities to be integrated into the global production network, pushing cities to successfully build stable and sustainable relationships in the international system. It may be argued that international relationships between cities can be only constructed based on respective resources, making the geoeconomic and geopolitical macro-trends steadily boil down to the city level. However, this logical relationship is only on the content-level, not up to the ontological level, which can not explain how cities and international interaction between them have become self-sustaining. In order to fill this theoretical gap, the author will draw insight from a variety of international relations theories, including International Relations theory, Globalization theory and Neo-medieval theory. International relations theory holds that the international system is in a state of anarchy, national-state monopolizing indivisible, exclusive authority; Globalization theory holds that with the expansion of the global market system, the authority of the nation-state as a territorial power is no longer overarching; and Neo-medieval theory views that the authority of sovereign powers has been divided, in which the global market system becomes closely connected to the provision of global public goods within a transnational society. These three theories provide a useful framework for observing the interaction between the nation-state, market economy and global community. International Relations theory tends to ignore the city due to its disciplinary characteristic of state of anarchy; Globalization theory explores the changing definitions of territory due to transnational economic forces, but the role of cities only in the sense of economic agency; and the Neo-medievalism doctrine recognizes the significance of the triangular relationship between nation-state, market economy and global community, but cities only as platform for this relationship rather than as independent entities.

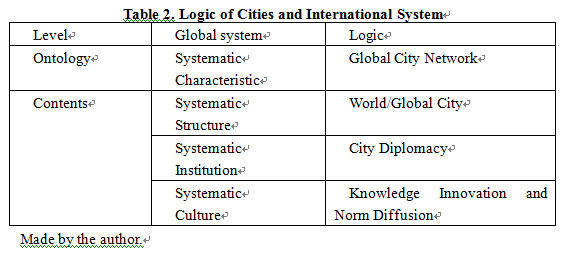

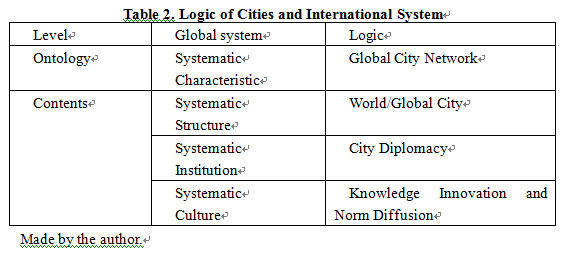

Therefore, the three branches of international theories fail to provide a full picture understanding of cities on the world stage as an independent actor. As Chinese Professor Qin Yaqin indicates, the international system can be broken down into two levels, the ontological level and the content level, therefore, if a systemic transformation occurs, both levels should manifest.[②] Ontological transformation means that basic units of the system are replaced, as in the case of the pre-modern international system changing into the Westphalia system, and the Westphalia system changing into the post-modern system. Content transformation mainly refers to the systemic structure (distribution of resources), systemic institution (transition from institutions losing their legitimacy), and systemic culture (the structure from old norms to new innovative ones). Constructing a framework for cities within the transformation of the international system should follow the same logic.

The key to constructing the logical relationship between cities and transformation of the international system is establishing ontological independence, which can only be gained from the weakening or even elimination of authority of the sovereignty nation-state. However weakening or elimination of a sovereignty state cannot be achieved by the city itself, but by external forces generated from a network, thus the formation of a network become vital. However, a new problem emerges, how such a city network come into formation. Jane Jacob posits that cities come in groups that need each other to prosper, a process of interaction between cities which creates complex divisions of labor in city economies,. In Jacob’s view, the city network could be created within individual countries, but this does not explain the question of how a world city network could be formed. The formation of world city network depends mainly on two dynamics: globalization and decentralization. For globalization, there are already too many existing explanations or accounts. Some theorists postulate that the history of globalization could be divided into five different phases—budding, early stages, taking-off, hegemony and then uncertainty. Since the late 1970s, with the information and communication revolutions of globalization sinking deeper, the flows of technology, capital, and people have increasingly become part of the same system.

When all of these things are clustered into one locale, cities can become the nodes of these flows. When capital inside one specific city is accumulated to a certain point, the driving forces of capital circulation and external linkages inevitably generate a new form of city network. Decentralization refers to the process of a central entity delegating functions and duties previously shouldered by the central entity down to its local counterparts. Decentralization does not occur at the will of cities or local governments the way economic growth does, but rather from the need for locales to be able to act on the complex issues brought on by the international system. Cities and local governments are closer to residents than central governments, thus in public services as education, health, poverty eradication, environmental risk-control, emergency management and other related policy areas, cities have various advantages in dealing with them. In essence, decentralization has then become a prerequisite for international stability.

Globalization provides the driving force of cities’ external linkages, with decentralization giving cities more autonomy , thus the combination of globalization and decentralization cause the horizontal flows of capital, information, technology, and talent from one region to another, as well as fostering a more vertical flow from the grassroots-up. Through these flows, the city network and cities themselves become the node for those flows. These flows require cities to interact, but it is still possible that city network can fall apart, namely unsustainable. Then, how such networks can be sustained? Actually, in formation of city networks, there are route, system and organization coming to being. Route here is defined as the infrastructure, such as telecommunications which facilitate connectivity; system is defined as the norms of inter-city interaction; and organization is defined as the coordinating bodies that often act as a global headquarters. Many theorists also think that there are three levels in city networks; system, node and sub-node. System here refers to the existing global political economy which cities exist within; node refers to cities themselves; and sub-node refers to financial and production services, such as branches of multinational corporations. The levels of system and node can only be connected through the level of sub-node. Following this logic, the route-level can lead to the system then organization-level, and from the sub-node to node and finally to the system-level — which leads to the sustaining of a city network. The formation and sustaining of a city network transfers the political and economic activities of cities directly to the world stage without any regulation of sovereignty. Under these circumstances, people and institutions are more inclined to re-orient themselves along the axis of a city-international system. Economic activities, information flows, modernization, and telecommunications generated by globalization would then be reshaped to suit the internal structure of cities. In this regard, the status of the nation-state in the international relations theory has been effectively weakened. Peter Taylor points out that city networks can no longer be neglected in the analysis of the international system[③]. The separation of city and state and the fragmentation of nation-states all make the nation-state increasingly reliant upon cities in connecting to the outside world, and thus the logical relationship of cities and the ontological transformation of international system comes to fruition.

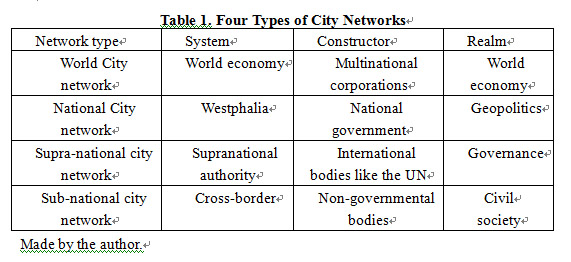

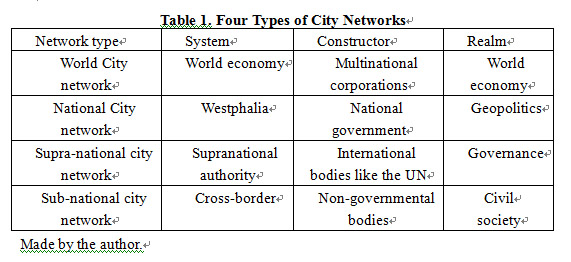

However, the scope would be limited to multinational corporations being defined as the primary actors in the construction of a world city network. For example, during the Cold War, national capital cities like Moscow, Beijing, Washington, D. C., and Brussels were largely excluded from world city networks, as at the time they were not home to the headquarters of many global corporations, thus the constructors of city networks have to be inclusive. Peter Taylor has described that there are several types of city networks nested within each other, which have coalesced[④]. For example, in addition to the world city network constructed by multinational corporations and their branches, there are national networks, supranational networks and subnational networks. National city networks are constructed by governmental bodies such as those in diplomatic spheres of influence based in national capitals, which by nature gives this type of network a divided geography, since such diplomatic spheres of influence represents sovereignty; supranational city network are constructed by intergovernmental organizations such as the World Bank, International Monetary Fund and World Trade Organization. Although the geographic location of inter-governmental institutions like these or of cooperation-based institutions such as humanitarian aid, engineering development, peacekeeping, and financial support are extremely dispersed, the management and implementation of their operations are confined to such cites as New York, Geneva, and Paris. The bureaucracy and the bottom-up decision-making processes of such institutions constitute the city as the prime actor in the network they form. Subnational city networks are constructed by non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Although there are various forms of actors and movements in global civil society, such as alliances, partnerships and cooperative programs, NGOs are still the most important actors which avail themselves to maximize influence in the public sphere. While NGOs are scattered across the global map, there is a clear trend of NGO concentration in cities like Nairobi, Brussels, London, New Delhi, Bangkok and Manila, thus this type of city network structure is as strongly dominated by cities as the other two types of networks.

The table above shows the four types of city networks that coalesce or are nested within each other, and constitute a new city network in modern political economic geography. With these laid out, it is important to explain how these different types of networks come to be nested within each other or coalesce. Helpful to explaining this is the concept of “flow of space,” introduced by Manuel Castells. In his book Rise of the Network Society, he points out that with the rise of informational society, the space of flows supersedes the space of places or locations. The space of flows is a material organization of time-sharing social practices that is formed by the combination of physical space and virtual space. Physical space refers to the traditional physical space in the sense of geography, including socio-economic activities and natural landscapes, while virtual space refers to the technological space of computers and digital telecommunications. Castells proposes the idea that the new spatial order, “space of flows,” is quite different from “space of places”, and “space of flows” is replacing “space of places” through “shared-time” and “flows.” However, how the process by which this replacement occurs needs to be addressed.[⑤]

According to David Harvey’s “time-space compression” theory, the key to integrating these flows is through the technological innovations that condense spatial and temporal distances.[⑥] Multinational corporations and their branches facilitate the flows of commodities, currency, services and even talent, while governmental bodies, inter-governmental bodies, and non-governmental bodies facilitate flows of information and public services. Eventually the economic space of flows, political space of flows and social space of flows are created. Although the political space of flows is largely dominated by cities and diplomatic spheres of influence, the social space of flows is led largely by geographically dispersed, mutually linked, multi-leveled individual and non-governmental organizations. The convergence of all these dimensions of space of flows through information technology and spatial infrastructure, then, demonstrates that the resources, people, information and activities inside cities are being gradually detached from the sovereignty of the nation-state. Thus, different dimensions of the international system, namely the world economy, Westphalia, global governance and civil society, are integrated into the same city network—and are becoming more self-sustaining.

II. Contents of a World City Network

If a world city network successfully builds the logical relationship between cities and the transformation of international system on the ontological level, then the content-level of such a network must be understood. The content-level of the international system is comprised of systematic structures, systematic institutions and systematic culture. Understanding the logical relationship between cities and the international system on the content-level requires elaborating on the role of cities within each.

The world city network is a type of network constituted by the flow of capital, information and people. However, different cities in the network have different forms, statuses and functions. Attempts to measure these differences can be found in the works of John Friedman, Peter Taylor, David Smith, BT Consulting and International Communication Corporation, Mark Abrahamson, the Mori Memorial Foundation, and others.[⑦] In August 2010, Foreign Policy magazine listed rankings of 65 world cities by business activities, human capital, information exchange, cultural experience, and political engagement. Business activity refers to the value of its capital markets, the number of Fortune Global 500 firms headquartered there, and the volume of goods that pass through the city.[⑧] Human capital refers to how well the city acts as a magnet for diverse groups of people and talent as well as the size of a city’s immigrant population, the quality of universities, the number of international schools, and the percentage of residents with university degrees. Information exchange refers to how well news and information is dispersed to the rest of the world. This dimension includes a number of international news bureaus, the level of censorship, the amount of international news in leading local papers, and the internet subscriber rate. Cultural experience refers to the level of diverse attractions for international tourists, including everything from how many major sporting events a city hosts to the number of performing arts venues and diverse culinary establishments it boasts, and not least the international sister city relationships it maintains. Political engagement measures the degree to which the city influences global policymaking and dialogue by examining the number of embassies and consulates, major think tanks, international organizations, and political conferences a city hosts.

These indexes properly reflect the position of a specific city in the world city network and its diversity of connectivity. However, it does not reflect the character of this connectivity. In my view, connectivity can be divided into three categories: Dominant, subordinate and neutral. Dominated connectivity is defined here as those cities which have the ability to manage and control worldwide production due to increasingly more value-added producer services—thus some cities exert more influence on the world economy than others; subordinate connectivity is defined as cities linking to the outside world that are more prone to rely on the central authority, like Beijing and Moscow; and neutral connectivity is defined as cities serving as the outside world’s bridge to a regional economy, such as Hong Kong. Varieties of connectivity of cities to the network show that the world city network structure is hierarchical. As Friedman points out, according to their function, cities can be divided into global financial centers, multinational centers, important national centers, and subnational regional centers. A global financial center can be regarded as a world city by John Friedman’s definition or as a global city by Saskia Sassen’s definition. According to Sassen’s narrative, the salient feature of the global cities is that these cities themselves are strategic hubs of political and economic influence, and can successfully turn productivity, political and economic conditions internal to the city into the practice of global influence and capability of resource allocation.[⑨]

Patrick Geddes and Peter Hall point out that the capability of global resource allocation can be translated into geo-political power of a nested country, thus the geographical dispersion and growing condition of world cities become a very important symbol of transformation in the systematic structure.[⑩] Immanuel Wallenstein believes the world system is comprised of three areas, core, semi-peripheral, and peripheral.[11] It is also reasonable that city networks follow the same logic, and can be divided into three segments. The geographical location of global cities such as New York, London and Tokyo seems to confirm this theory. However, this simple, static corresponding relationship has ignored the important fact that the world city network is full of uncertainty as world economic cycles alternatively centralize and decentralize. When centralization occurs, the controlling capability of global cites significantly increases; when decentralizing or diffusing of influence occurs, production shifts from developed to developing countries, the resources flowing from global cities to their periphery, thus subnational regional centers, important national centers and multinational centers are gradually moving up to the global center. Thus, in the same network, there emerges a group of cities with the aspiration of becoming global cities, which are referred to as rising world cities. These rising world cities clearly indicate that city networks can strongly shape the international structure beyond the logic of North-South and simple struggling among nations. Peter J. Taylor, Michael Hoyler and Dennis Smith also confirm that the geography of explosive economic growth and dynamic cities are front-loaded in the cycle of hegemonies and cities generating the myriad networks that produce hegemony. Whereas hegemony is not exercised by a single country, creative city networks are initially concentrated within one single state. Thus, prosperous cities are, to some extent, symbols of transformation of the systematic structure.[12]

There are also historical evidences listed by numerous professionals. Joel Kotkin notes that any successful city must have three characteristics of “sacredness, security, and economy.”[13] Fernand Braudel indicates that the city-centered world economy has been allowed to better integrate into their regional economies by the economic and trade networks of cities such as Venice, Antwerp, and Amsterdam.[14] Jacques Attali notes that the history of European economic growth has always been led by its strongest cities.[15] King and other relevant scholars apply Wallenstein’s dependence theory to explore how the world urban system can be viewed as a replication of the world system,[16] and point out that historical city trade networks illuminated the market economy by absorbing economic resources that had become “disembedded” from society.[17] Arrighi uses Marxism to explain that Genoa, Amsterdam, London, New York and other leading cities actually represent the capitalist cycle of accumulation and hegemony.[18] Historically, there indeed existed a strong correlation between rising world cities and the rise of their respective countries.

If rising world cities or cities initially with prosperous economy can influence and to some extent change the systematic structure, the way to promote the transformation of international institutions is through city diplomacy. Liberal internationalists insist that the international system could be stable mainly due to international institutions which combine different, even conflicting, interests of diverse actors at all levels. They describe that this is owed to all kinds of formal and informal international regimes. However, multilateralism at the national level is not always effective, encountering “democracy deficit,” “lack of driving forces,” “low efficiency,” and “unclear outcome,” thus the support from other various types of actors become necessary. Cities may use local-central channels to express ideas to the national authorities, draw insights from the underlying civil society, outwardly participate in international affairs, and incorporate those ideas into local policy and practice. Thus, cities have the potential to be the leaders, promoters and practitioners of multilateralism on a very special level. Like nations, cities have policy instruments to promote multilateralism, such as sister cities, inter-cities organizations, norm initiatives (e.g., Information Dissemination, Consulting, and Mass Communication Campaign), effective move on their own or form willing coalitions, etc. Such instruments fall under the category of city diplomacy. City diplomacy can be defined as “the institution and process by which cities or local governments in general, engage in relations with actors on an international political stage with the aim of representing themselves and their interests to one another,” and has various dimensions including security, development, economic, and culture. [19]

Compared with national diplomacy, city diplomacy has some very uncommon characteristics--non-sovereign in constitutional terms, not political in function, and intermediary in action. The rise of city diplomacy beckons academic analysis of international relations to explore how international institutions could directly affect local and social practices. World cities have been able to directly supply global public goods to international system in three ways: Firstly, the innovative practices and institutional capacity of world cities not only provide services for the local communities and national economy, but also manage transnational and trans-regional relationships and maintain global order together with other governmental and non governmental bodies; Secondly, the post-Fordism of production brings together the world-leading technology-finance-management elites, and these elites are directly involved with global affairs, positively resolving such issues as climate change, financial crisis, non-traditional security and humanitarian disasters. The decisions made by transnational corporations’ headquarters located in New York and Tokyo greatly affect environmental practices and working conditions in the third word; Thirdly, world cities could maintain direct relationships with other international bodies, promoting and supporting new transnational political processes, linking micro-political processes with macro-political trends. For instance, in the operation of the Shanghai World Expo, the Shanghai municipal government successfully built a very good relationship with the United Nations bodies.

However, city diplomacy has not been legally recognized and is bound by domestic frameworks, thus belonging to “the other world of world politics”. This saying neglects the fact that both sovereignty nations and cities are in the diplomatic environment which is increasingly complex, multi-layered and multi-centered, as well as the fact that the development or implementation of international policies increasingly needs the participation and support of cities and local governments. The contribution of cities to international institutions can be explicit and implicit. Explicitly, the cities accommodate international institutions, for example, the Rio 20 Summit of Sustainable Development place cities as one of the seven issues to be addressed. Implicitly, those conventions and agreements that do not have cities’ contents while achieving the goals largely rely on cities. The best example of this is the carbon mandatory reduction of the Kyoto Protocol, in which low carbon cities have become a crucial part of the process. The second form refers to the cities identified to be involved with programs and activities initiated by inter-governmental organizations, such as the UN, World Bank, UNEP, etc. Many cities such as Amsterdam and Atlanta have established a city bureaucracy in charge of the city’s foreign affairs, especially in economic and trade, cultural exchanges and as liaisons with other world cities. In order to meet the general needs of cities and local governments, the United Nations established the UN-Habitat responsible for urban habitation in 2002. In 2004, the organization of United Cities Local Governments was established.

The transformation of the international system on the content-level is also reflected in the changing of norms, while the role of cities in this process could be played as an entrepreneur or disseminator. According to the norm dynamic model proposed by Martha Finnemore and Kathryn Sikkink, any norm would evolve in three stages, emergence, cascade, and internalization.[20] Emergence means norm entrepreneurs influencing state actors by constructing cognitive frames while competing with other normative interests. Cascading refers to NGOs, social movements and civil society networks which provide an arena in which norms can become institutionalized, and this stage does not occur until one-third of total states adopt the norm when a “critical mass” of states is influenced. Internalization means that norms become “taken-for-granted” with the result that they are both powerful and hard to discern. According to their explanation, norm entrepreneurs are actors, and this actor--whether a normative community or not, state or non-state, self-aware or not--must have a clear understanding of what is good or appropriate behavior. Then, the question is how the new norms emerge? Barry Buzan and Olive Weaver from the English School offer the answer that, when old norms cannot deal with new challenges posed by new issues, there emerge new necessities for norm innovation, and these necessities go through “securitization”. According to securitization theory, the authority could redefine some issues as existential threats, and around these existential threats, conventions and routines evolve to new norms.[21] Since the end of WWII, there have emerged many new norms. Some of them are associated with liberalization of commerce that is the very foundation of the WTO Charter; some of them are related with the newly coined concepts “sustainable development”, “precautionary principle” and “common but differentiated responsibility” which the Declaration on Human Environment and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change reflect. Therefore, cities hosting a certain population, with a certain history, and having a certain value system, have the ability to be norm entrepreneurs.

Norm entrepreneur are not merely governmental actors; on some occasions transnational corporations and individuals also have the same capacity. The National Intelligence Council’s report, Global trends 2030: Alternative Worlds, points out that individual empowerment will accelerate owing to the poverty reduction, growth of the global middle class, greater educational attainment, widespread use of new communications and manufacturing technologies, and health-care advances. Under these conditions, the capacity of cities to innovate, shape, and disseminate norms is growing.[22] Here we take the environmental issues as an example. Cities are piled up with large quantities of material substances, and blamed for carbon emissions and environmental disasters which pose a threat to the survival and continuation of the cities themselves. Environmental securitization enables cities to show the normative significance of their environmental strategy, measures and policies. And if these strategies, policies and measures are successful, newly created norms are to be spread. As a civil power, cities do not have mandatory power to promote norms. Instead, cities can motivate someone else to keep up with their expectation through material assistance.

Cities in South Africa abandoning apartheid policy early can get considerable material goods from other friendly cities. Persuasion requires cities to take initiatives. Another example would be in October 2005, when 18 representatives of world’s major cities gathered to establish a special alliance in tackling climate change called C40. C40 takes full advantage of the various types of city networks, linking low carbon and environmental protection with national security; effectively promoting the values of low carbon practices on the international level, increasingly committing to embarking on low carbon transitions. It has been pointed out that those newly created values and norms may not conform to the foreign policy of respective sovereign nations or mainstream values of human rights, liberty and democracy. During the Cold War, a coalition of over 900 cities and towns in the U.S. passed a resolution that called for the end to the U.S.-Soviet arms race, which was contrary to the U.S.’ foreign policy of that time. Those norms created by cities spread through world city networks and would gradually impact the whole international system. The more actors accept new norms, the more possibility, momentum and forces that the transformation of the international system can absorb.

Multilateralism on the city-level or city diplomacy makes the national system and institution fragmented, thus cities are more and more directly involved with the operation of international institutions. Innovation and diffusion of norms through securitization of global issues finally make great changes in the norm clusters of the international system. Whether global cities turning the productivity into the practice of global control, multilateralism on the cities-level or city diplomacy, or norm entrepreneur and diffusion which cannot be separated from the world city network, they all indicate the importance of the network in promoting the ontological transformation of cities and the international system. When cities not only invest, attract multitude of labor forces, and advance technological revolution for themselves, but also provide practical reference and role of model for others, when cities could affect public policies of each other, when the residents realize the existence of network, then produce the shared knowledge even cohesiveness, the world city network finally become independent and undermine the unity of the national authority, thus the transformation of the international system become inevitable in nature.

III. The Creation of Scalar Politics

A world city network constructs the ontological relationship between cities and the transformation of the international system. Meanwhile the global cities, city diplomacy and knowledge innovation and diffusion together transform the international system on the content level.

Sociology indicates that any network has four dimensions: structures, resources, norms and social dynamics. The same is true for the city network, and it is these four dimensions that enable the world city network to create a new political space.

Through the social dynamic, the anarchy of the international system has been weakened. The state of anarchy lays the foundation of the international system. If the state of anarchy is diminished, the essence of the international system would be transformed. Although the concept of anarchy has many interpretations, these different understandings at least could reach a consensus on the basis of “lack of absolute authority to manage sovereignty.” Human nature creates the original common needs, then shape norms, entrepreneur values as well as conventions, moralities, thus the international system is not in the state of anarchy but in the anarchical society. In an anarchical society, a world city network still cannot manage state actions, let alone going beyond the sovereign authority, but the information and communication infrastructure, institutional arrangements embedded in “space of flows,” has been useful in promoting mutual understanding and commitments among all types of actors. In Robert Keohane and Joseph Nye’s words, the social attribute of the international system become thickened; the extent of anarchy is lessened.[23] Some people even point out that the thickness of sociality of the international system has been largely dependent on the cities’ internalization of people’s common life, thus cities become the main area of norms competition. Actually, as the norm dynamic model indicates, norms can be innovated in a spontaneous informal way or very formal way which further up to certain groups and organizations. Channels and capabilities of norm diffusion have been nested in “space of flows,” thus the dynamic within networks, including internal communication among network and external communication with the international system, become more important.

The institutional inter-city cooperative platform has become a new issue in the international system while the policy network generated from the city network is increasingly becoming a sort of structure in the international system. The diversity of city networks clearly indicates the complexity of the urban environment, and the space of flows becomes part of public policy making. This difference can be explained with the following four points: (1) as information, goods and people flow faster, uncertainty is getting more prominent; (2) the nexus of diverse policy issues causing a slight move in one direction may affect the situation as a whole; (3) with the growing capability of autonomous actors, and the higher frequency of interactions of all sorts of organizations, the legitimacy of policy intervention is unprecedented weakened; (4) as the policy and issue nexus become more significant, one policy often in effect, even de facto, veto the implementation of another policy. Under this situation, the governments’ leverage in mobilizing all the policy resources is getting lower and problem-solving requires the collective action of diverse actors and stakeholders, thus highlighting the importance of working relationships among all sorts of actors, governments, NGOs, enterprises and individuals to eventually construct the policy network. Rhodes states that the policy network is portrayed as sets of interdependent organizations which have to exchange resources to realize their goals. Relationships within networks are characterized by their power-dependent nature.[24]

On one hand, the network is constructed around an issue-area, on the other, the policy network is encased into the national institution and globalization, thus a sort of intertwinement emerges making the city eventually developing three types of abilities: integration, consolidation and extension. Integration means cities can attract a variety of resources and actors around a particular issue, then an appropriate policy framework is constructed. David Held states that a city can effectively coordinate and control transnational activities through provision of infrastructure and professionals.[25] Consolidation means integration of issue-areas and relative experience providing. Nowadays, new issues endless emerge am, low politics such as environment-poverty-unemployment and high politics such as energy-politics-military are in nexus, but the lack of a comprehensive policy framework often leads to limited progress. However, many issues do not necessarily need a brand-new policy framework to solve, largely dependent on solutions on the local level, while the issue-link on the local level is relatively simple. Compared with the state, cities handle the contradiction between economic recovery and environmental abatement more easily. Thus low carbon cities become a very simple way to realize low carbon development. The extension means leverage effect. A city network bestows on cities dual identities of domestic and international functions, and such dual identities again give cities additional space and flexibility. Between requirements of hosting governments and the outside networks, cities have more opportunities to determine which one is worthwhile. Indeed, more cities have more opportunities to be heard, and to influence the values, beliefs and principles of domestic/outside people by the “Boomerang effect.” Besides, through effective communication and leverage effect, cities can also maximize the abilities to organize actors with global interests. Due to three types of abilities of cities mentioned above, some large developing countries especially China aggressively link the nation with the global production network or space of flow through urbanization strategy, and obtain new international strategic space through building global cities.

The world city network becoming a new analyzing level in international system, scalar politics is clearly visible. In the common sense, the advantage of such a network cannot derive from a hierarchical structure but from horizontality and openness. With more and more cities weaved into the network, all sorts of activities and events inside a city are directly exposed to other cities and the international system, thus new scalar politics becomes relevant. Castells thinks that globalization and informatization lead to the rise of local activities on the global level, and that the micro-environments with a global span and locality are linked with each other spontaneously.[26] The local can use this linkage to implement old strategies like nationalism as well as new organizational and operational models such as public diplomacy. Saskia Sassen points out that urban space indeed accommodates large numbers of activities not filtered through the formal political system, including silent sitting, demonstrations, marches and other various forms of discontenting activities. These activities are classified into three categories.[27]

The first category is marked with local goals. The local goals can be specified as environmental protection, factory strike, or local production, etc. But the knowledge of these issues is still from other places. The second category is marked with national goals. National goals can be specified as some movements like “Occupy Wall Street,” the demonstration against Gaddafi in the city of Tripoli, or March against Putin in Moscow. Obviously, these movements have very clear political characteristics but cannot be exempt from the influence of the financial crisis and outside interference. The third is marked with systematic goals. Systematic goals can be specified with transnational activities conducted by the WTO, IMF, or transnational corporations, thus local activities have become an integral part of the global network. It needs stressing that the scalar politics shaped by the “space of flows” do not necessarily follow the “local-national-global” path or the opposite, and some very “emboldened” could entirely manipulate or operate at several levels simultaneously. Various actors inside cities do not mean to acquire specific power or material interests, but indeed get effective support materially or emotionally through interdependence or “space of flow”. The interdependence empowers actors to voluntarily get clustered, focus on the locality then operate in the global network, making cities eventually embedded into the multi-layer spatial governance and institutional setting. Therefore, locality not only acquires globality but also becomes part of the global circuit and transnational network.

IV. Possible Negative Consequences

The success of the constructing of cities and transformation of the international system is not unconditional. In addition to globalization, informatization and the coordination of national public polices, the developmental strategy of individual cities or the effort of cities linking themselves to the global circuit of political economy also play a pivotal role. In the first half of the 20th century, almost every big city had a leading industrial base, and in the next half these cities encountered various sorts of problems, such as production decline, competitiveness loss, and unemployment or continuous immigration. Under the influence of neo-liberalism, the urban elites think that only the growth strategy which prompts cities to be connected to the circuit of global political economy can restore the status of cities in the network. Actually some cities with clear intentions, swift action and good planning indeed have made great success, and soon become prominent city-regions or even world/global cities, such as Manchester in the UK, Miami in the U.S., and those without a successful strategy and transformation such as the city of Detroit are slowly backsliding. It needs to be stressed that a growth strategy does have costs and the correlation of cities and the circuit of global political economy is not always beneficial. In achieving the transformation of international transformation, cities do encounter technical risks as well as ethical problems.

A technical risk, by definition, is a type of plight which is caused by the technologies widely applied in the development of cities and this type of risks can very seriously affect the transformation of the international system. City as a man-made product is actually a type of entity of material production, consumption, distribution woven by a series of technologies. In order to maintain normal functioning of this network, infrastructure such as transportation, telecommunications as well as large amounts of natural substances are inevitable, thus infrastructure and resource extraction technologies become the prerequisite for urban development. The endogenous growth model in economics theories points out that technological breakthroughs are intertwined with the process of economic growth. Under the condition of perfect market competition various resources are priced by the equilibrium of supply and demand, and the technological innovator responds sensitively by the price signal, then primary technological innovation happens. These newly creative technologies ultimately alter input-output efficiency and maximize resource allocation, then promote economic growth.

Economic growth and technological innovation mutually push each other in a spiral upward, become deeply embedded into the urban development, then those technologies spread to the international system through the world city network. Technologies, particularly core technologies (such as atomic energy and low carbon technologies), have direct physical effects on respective nations, possibly changing the balance of national political power, creating channels or opportunities for non-state actors to be directly involved in the international system, and facilitating the spread of values, principles and beliefs. Castelles states that technological innovation leads to the rise of local activities at the global level which further erode traditional territorial frontiers. “Technology itself becomes global power”, and technology eventually become a way of life.[28] Ulrich Beck in his book Risky Society points out that the evolving technologies make this world full of uncertainties and risks.[29] Anthony Giddens holds the similar view that the modern knowledge constantly makes risks, and taking risks becomes a way of life. Moderate risks may be conducive to social creativity and knowledge innovation, yet when risks evolve into pervasive and persistent fear or horror, the risks themselves would be politicized and securitized and rise to be the focus in the international system. “Urban transport, infrastructure, buildings and industrial location then all the urban technologies.”[30] No matter daily risks as transportation, or security risks as environmental and nuclear disaster, or all sorts of disease risks as SARS, occur in one city, they will soon spread to other cities, and finally affect the whole international system. For the reason mentioned above, the linkage among economy, technologies and risks is embedded into the interaction of cities and the international system. Thus risks are not occasional events beyond the \ economy or society, but have become the core component of the international system. However, the most important way to deal with risks is still through technological innovation. Sovereign nations in seeking security in the sense of political economy and cultural psychology and minimizing losses have to make appropriate policy responses, mainly through operational policies and measures (such as technical standards and guidelines for insurance). Technological innovation not only promotes urban development and power transition, but also brings vulnerabilities and risks to human being. Thus it needs to be emphasized that risk discovery, risk prevention and risk cooperation originating from city development are non-traditional security issues that the international system has to take seriously.

Moral hazards refer to the negative externalities that cities produce in the process of achieving their strategic goal, and these negative externalities need to be remedied by other actors. The growth strategies which aim to link cities with the circuit of global political economy necessitate the continuous input of resources and values to cities, then have output from cities. However, due to various reasons, this input-output balance cannot always be sustained. Cities always have the incentives to pass the buck to the outside world. This sort of motivation is specifically embodied in the two issues, the “financial crisis “and “climate change”. The financial crisis which broke out in the Wall Street had a root in the neo-liberal growth strategy manipulated by the urban elites. This crisis not only distorted the global economic order, causing many cities’ asset value diving, but also compelled related nations to take collective actions like G20 providing global public goods to make circuits of global political economy function as usual. Climate change is the toughest issue in the international system, and its threat to the survival and security compels the international community to cut carbon emission based on comprehensive consideration of economic growth, intergenerational equity and ecological vulnerability, thus competition for environment-sustaining capacity and development space gets increasingly fierce. Although nations take primary accountability of climate regime negotiation, scientific evidence indicates that whether in mitigation or adaptation, cities have become an crucial part. Data show that cities only occupy a small proportion of global land, releasing large proportions of total amount of carbon. It is reasonable that the emission volume decides mitigation obligations. However, it is not always clear as indicated. Dhakal, having comparatively analyzed the four cities of Beijing, Shanghai, Seoul and Tokyo, found out that carbon emission per capita in Beijing was 30 percent higher than Tokyo, though Tokyo was 46 percent higher than Beijing if the whole chain of products and services were counted in.[31] This calculation means cities in developed countries transfer high-emission industries to cities in developing countries, and then the direct emission of cities like Tokyo is one third less than that of all the stuff consumed. Whether the responsibilities of carbon reduction lie with the producer or consumers becomes one of the main challenges that international institutions and international norms must encounter. Both the financial crisis and environmental change arisen from cities reveals that the ethical problems cities bring to the international system cannot be easily solved, and they have become one of the driving forces of transformation of the international system.

Cities construct logical relationships with the international system through world city networks; meanwhile, they bring technological risks and ethical problems. Thus the international system has more non-traditional issues and these new non-traditional issues further transform the international system, although they cannot overthrow the whole international system,. Of course, there is no need to point that these new issues and pressures will assemble new energy and momentum than ever in advancing transformation of the international system.

V. Conclusion

A city, by definition, is essentially a “theater of social activities”. Since it is a theatre, too many things must be accommodated, such as arts, politics, education, and businesses. With economies becoming disembedded from society and political institutions, political attributes are gradually becoming monopolized by nations and cities. As the rise of space of flows constituted by globalization and informatization, cities are irreversibly replacing nations to become the organizational architecture of global spatial economy, and at the same time, the world city network is gradually formed. Peter Taylor points out that city networks could be divided into four types, namely world, national, supranational, sub national, with the coalescence of “space of flows.”. The emergence of world city networks indicates that outside sovereign states there exists a new organizational architecture in the international system consisting not merely of global spatial economy, but also new political space alleviating the extent of anarchy, forming policy networks and scalar politics. Within a world city network, there are always some nodes with more influence and capacity which can be called world/global cities. Saskia Sassen points out that global cities are rising from the centralized management of the dispersed world production structure.[32] Since the very beginning of industrialization, world cities cannot be separated from geo-political struggle among nations. But from cases of climate change, financial crisis, and epidemics, it is not difficult to find that world cities also have the capacity to be engaged with global governance. Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri in the book Empire state that inside the international system there emerges a new form of sovereignty, discrete, networked without any center, only the nodes are connected to each other, called “Empire”. Empire fully adapts to the needs of world market competition, capital circulation and post-Ford mode of production, produces new differences in power and wealth distribution through the existing hierarchical operation, then become the most appropriate form of the new liberalism.[33] Through the elaboration above, it is not difficult to find out that world/global cities are the integral parts of this political form. As cities holding more than half of the population in the year of 2008, the neglect of cities by the international system may lead to very serious consequence.

The fact that cities, city networks and global cities are an integral part of this new political form indicates that the attributes of politics of cities offer new inspiration and ideas to Chinese people. Currently, China is in the process of massive urbanization and aggressively shaping the cities of Beijing and Shanghai into global cities. This process is better understood as an economic development, resource reallocation and capital flow management, and not having any sense of geo-politics and governance. Thus we must pay more attention to the political attributes of cities, focusing on the fusion of fierce geo-political struggles and the impact of global governance. Here we suggest that grand diplomacy and multi-layered diplomacy first proposed by Brian Hocking[34], pay much attention to multi-tiered stage infused by civil society, local government, and the international system. For urban leaders, residents, and policy makers, those who try to be actively connected the international system, must focus on the diversity of types of city network, taking various measures to attract multinational corporations as well as international organizations, foreign government offices and major non-governmental organizations. Of course, the success in large part lies in information infrastructure and convenient speeding transportation. As for national leaders, the traditional reciprocal diplomacy obviously cannot meet the demands of the new situation. Here we propose to lift the importance of cities and sub-governmental diplomacy and proactively embark on public diplomacy with necessary regulations and proper tightness in accordance with different actors and agencies.

The increasing decentralization of global resource allocation is a natural mechanism for integrating more cities into the circulatory system of the world economy. Jane Jacobs links dynamic cities to economic development, in which cities come together in groups that need each other to prosper.[①] Increasingly fierce competition on the global market compels cities to be integrated into the global production network, pushing cities to successfully build stable and sustainable relationships in the international system. It may be argued that international relationships between cities can be only constructed based on respective resources, making the geoeconomic and geopolitical macro-trends steadily boil down to the city level. However, this logical relationship is only on the content-level, not up to the ontological level, which can not explain how cities and international interaction between them have become self-sustaining. In order to fill this theoretical gap, the author will draw insight from a variety of international relations theories, including International Relations theory, Globalization theory and Neo-medieval theory. International relations theory holds that the international system is in a state of anarchy, national-state monopolizing indivisible, exclusive authority; Globalization theory holds that with the expansion of the global market system, the authority of the nation-state as a territorial power is no longer overarching; and Neo-medieval theory views that the authority of sovereign powers has been divided, in which the global market system becomes closely connected to the provision of global public goods within a transnational society. These three theories provide a useful framework for observing the interaction between the nation-state, market economy and global community. International Relations theory tends to ignore the city due to its disciplinary characteristic of state of anarchy; Globalization theory explores the changing definitions of territory due to transnational economic forces, but the role of cities only in the sense of economic agency; and the Neo-medievalism doctrine recognizes the significance of the triangular relationship between nation-state, market economy and global community, but cities only as platform for this relationship rather than as independent entities.

Therefore, the three branches of international theories fail to provide a full picture understanding of cities on the world stage as an independent actor. As Chinese Professor Qin Yaqin indicates, the international system can be broken down into two levels, the ontological level and the content level, therefore, if a systemic transformation occurs, both levels should manifest.[②] Ontological transformation means that basic units of the system are replaced, as in the case of the pre-modern international system changing into the Westphalia system, and the Westphalia system changing into the post-modern system. Content transformation mainly refers to the systemic structure (distribution of resources), systemic institution (transition from institutions losing their legitimacy), and systemic culture (the structure from old norms to new innovative ones). Constructing a framework for cities within the transformation of the international system should follow the same logic.

The key to constructing the logical relationship between cities and transformation of the international system is establishing ontological independence, which can only be gained from the weakening or even elimination of authority of the sovereignty nation-state. However weakening or elimination of a sovereignty state cannot be achieved by the city itself, but by external forces generated from a network, thus the formation of a network become vital. However, a new problem emerges, how such a city network come into formation. Jane Jacob posits that cities come in groups that need each other to prosper, a process of interaction between cities which creates complex divisions of labor in city economies,. In Jacob’s view, the city network could be created within individual countries, but this does not explain the question of how a world city network could be formed. The formation of world city network depends mainly on two dynamics: globalization and decentralization. For globalization, there are already too many existing explanations or accounts. Some theorists postulate that the history of globalization could be divided into five different phases—budding, early stages, taking-off, hegemony and then uncertainty. Since the late 1970s, with the information and communication revolutions of globalization sinking deeper, the flows of technology, capital, and people have increasingly become part of the same system.

When all of these things are clustered into one locale, cities can become the nodes of these flows. When capital inside one specific city is accumulated to a certain point, the driving forces of capital circulation and external linkages inevitably generate a new form of city network. Decentralization refers to the process of a central entity delegating functions and duties previously shouldered by the central entity down to its local counterparts. Decentralization does not occur at the will of cities or local governments the way economic growth does, but rather from the need for locales to be able to act on the complex issues brought on by the international system. Cities and local governments are closer to residents than central governments, thus in public services as education, health, poverty eradication, environmental risk-control, emergency management and other related policy areas, cities have various advantages in dealing with them. In essence, decentralization has then become a prerequisite for international stability.

Globalization provides the driving force of cities’ external linkages, with decentralization giving cities more autonomy , thus the combination of globalization and decentralization cause the horizontal flows of capital, information, technology, and talent from one region to another, as well as fostering a more vertical flow from the grassroots-up. Through these flows, the city network and cities themselves become the node for those flows. These flows require cities to interact, but it is still possible that city network can fall apart, namely unsustainable. Then, how such networks can be sustained? Actually, in formation of city networks, there are route, system and organization coming to being. Route here is defined as the infrastructure, such as telecommunications which facilitate connectivity; system is defined as the norms of inter-city interaction; and organization is defined as the coordinating bodies that often act as a global headquarters. Many theorists also think that there are three levels in city networks; system, node and sub-node. System here refers to the existing global political economy which cities exist within; node refers to cities themselves; and sub-node refers to financial and production services, such as branches of multinational corporations. The levels of system and node can only be connected through the level of sub-node. Following this logic, the route-level can lead to the system then organization-level, and from the sub-node to node and finally to the system-level — which leads to the sustaining of a city network. The formation and sustaining of a city network transfers the political and economic activities of cities directly to the world stage without any regulation of sovereignty. Under these circumstances, people and institutions are more inclined to re-orient themselves along the axis of a city-international system. Economic activities, information flows, modernization, and telecommunications generated by globalization would then be reshaped to suit the internal structure of cities. In this regard, the status of the nation-state in the international relations theory has been effectively weakened. Peter Taylor points out that city networks can no longer be neglected in the analysis of the international system[③]. The separation of city and state and the fragmentation of nation-states all make the nation-state increasingly reliant upon cities in connecting to the outside world, and thus the logical relationship of cities and the ontological transformation of international system comes to fruition.

However, the scope would be limited to multinational corporations being defined as the primary actors in the construction of a world city network. For example, during the Cold War, national capital cities like Moscow, Beijing, Washington, D. C., and Brussels were largely excluded from world city networks, as at the time they were not home to the headquarters of many global corporations, thus the constructors of city networks have to be inclusive. Peter Taylor has described that there are several types of city networks nested within each other, which have coalesced[④]. For example, in addition to the world city network constructed by multinational corporations and their branches, there are national networks, supranational networks and subnational networks. National city networks are constructed by governmental bodies such as those in diplomatic spheres of influence based in national capitals, which by nature gives this type of network a divided geography, since such diplomatic spheres of influence represents sovereignty; supranational city network are constructed by intergovernmental organizations such as the World Bank, International Monetary Fund and World Trade Organization. Although the geographic location of inter-governmental institutions like these or of cooperation-based institutions such as humanitarian aid, engineering development, peacekeeping, and financial support are extremely dispersed, the management and implementation of their operations are confined to such cites as New York, Geneva, and Paris. The bureaucracy and the bottom-up decision-making processes of such institutions constitute the city as the prime actor in the network they form. Subnational city networks are constructed by non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Although there are various forms of actors and movements in global civil society, such as alliances, partnerships and cooperative programs, NGOs are still the most important actors which avail themselves to maximize influence in the public sphere. While NGOs are scattered across the global map, there is a clear trend of NGO concentration in cities like Nairobi, Brussels, London, New Delhi, Bangkok and Manila, thus this type of city network structure is as strongly dominated by cities as the other two types of networks.

The table above shows the four types of city networks that coalesce or are nested within each other, and constitute a new city network in modern political economic geography. With these laid out, it is important to explain how these different types of networks come to be nested within each other or coalesce. Helpful to explaining this is the concept of “flow of space,” introduced by Manuel Castells. In his book Rise of the Network Society, he points out that with the rise of informational society, the space of flows supersedes the space of places or locations. The space of flows is a material organization of time-sharing social practices that is formed by the combination of physical space and virtual space. Physical space refers to the traditional physical space in the sense of geography, including socio-economic activities and natural landscapes, while virtual space refers to the technological space of computers and digital telecommunications. Castells proposes the idea that the new spatial order, “space of flows,” is quite different from “space of places”, and “space of flows” is replacing “space of places” through “shared-time” and “flows.” However, how the process by which this replacement occurs needs to be addressed.[⑤]

According to David Harvey’s “time-space compression” theory, the key to integrating these flows is through the technological innovations that condense spatial and temporal distances.[⑥] Multinational corporations and their branches facilitate the flows of commodities, currency, services and even talent, while governmental bodies, inter-governmental bodies, and non-governmental bodies facilitate flows of information and public services. Eventually the economic space of flows, political space of flows and social space of flows are created. Although the political space of flows is largely dominated by cities and diplomatic spheres of influence, the social space of flows is led largely by geographically dispersed, mutually linked, multi-leveled individual and non-governmental organizations. The convergence of all these dimensions of space of flows through information technology and spatial infrastructure, then, demonstrates that the resources, people, information and activities inside cities are being gradually detached from the sovereignty of the nation-state. Thus, different dimensions of the international system, namely the world economy, Westphalia, global governance and civil society, are integrated into the same city network—and are becoming more self-sustaining.

II. Contents of a World City Network

If a world city network successfully builds the logical relationship between cities and the transformation of international system on the ontological level, then the content-level of such a network must be understood. The content-level of the international system is comprised of systematic structures, systematic institutions and systematic culture. Understanding the logical relationship between cities and the international system on the content-level requires elaborating on the role of cities within each.

The world city network is a type of network constituted by the flow of capital, information and people. However, different cities in the network have different forms, statuses and functions. Attempts to measure these differences can be found in the works of John Friedman, Peter Taylor, David Smith, BT Consulting and International Communication Corporation, Mark Abrahamson, the Mori Memorial Foundation, and others.[⑦] In August 2010, Foreign Policy magazine listed rankings of 65 world cities by business activities, human capital, information exchange, cultural experience, and political engagement. Business activity refers to the value of its capital markets, the number of Fortune Global 500 firms headquartered there, and the volume of goods that pass through the city.[⑧] Human capital refers to how well the city acts as a magnet for diverse groups of people and talent as well as the size of a city’s immigrant population, the quality of universities, the number of international schools, and the percentage of residents with university degrees. Information exchange refers to how well news and information is dispersed to the rest of the world. This dimension includes a number of international news bureaus, the level of censorship, the amount of international news in leading local papers, and the internet subscriber rate. Cultural experience refers to the level of diverse attractions for international tourists, including everything from how many major sporting events a city hosts to the number of performing arts venues and diverse culinary establishments it boasts, and not least the international sister city relationships it maintains. Political engagement measures the degree to which the city influences global policymaking and dialogue by examining the number of embassies and consulates, major think tanks, international organizations, and political conferences a city hosts.

These indexes properly reflect the position of a specific city in the world city network and its diversity of connectivity. However, it does not reflect the character of this connectivity. In my view, connectivity can be divided into three categories: Dominant, subordinate and neutral. Dominated connectivity is defined here as those cities which have the ability to manage and control worldwide production due to increasingly more value-added producer services—thus some cities exert more influence on the world economy than others; subordinate connectivity is defined as cities linking to the outside world that are more prone to rely on the central authority, like Beijing and Moscow; and neutral connectivity is defined as cities serving as the outside world’s bridge to a regional economy, such as Hong Kong. Varieties of connectivity of cities to the network show that the world city network structure is hierarchical. As Friedman points out, according to their function, cities can be divided into global financial centers, multinational centers, important national centers, and subnational regional centers. A global financial center can be regarded as a world city by John Friedman’s definition or as a global city by Saskia Sassen’s definition. According to Sassen’s narrative, the salient feature of the global cities is that these cities themselves are strategic hubs of political and economic influence, and can successfully turn productivity, political and economic conditions internal to the city into the practice of global influence and capability of resource allocation.[⑨]

Patrick Geddes and Peter Hall point out that the capability of global resource allocation can be translated into geo-political power of a nested country, thus the geographical dispersion and growing condition of world cities become a very important symbol of transformation in the systematic structure.[⑩] Immanuel Wallenstein believes the world system is comprised of three areas, core, semi-peripheral, and peripheral.[11] It is also reasonable that city networks follow the same logic, and can be divided into three segments. The geographical location of global cities such as New York, London and Tokyo seems to confirm this theory. However, this simple, static corresponding relationship has ignored the important fact that the world city network is full of uncertainty as world economic cycles alternatively centralize and decentralize. When centralization occurs, the controlling capability of global cites significantly increases; when decentralizing or diffusing of influence occurs, production shifts from developed to developing countries, the resources flowing from global cities to their periphery, thus subnational regional centers, important national centers and multinational centers are gradually moving up to the global center. Thus, in the same network, there emerges a group of cities with the aspiration of becoming global cities, which are referred to as rising world cities. These rising world cities clearly indicate that city networks can strongly shape the international structure beyond the logic of North-South and simple struggling among nations. Peter J. Taylor, Michael Hoyler and Dennis Smith also confirm that the geography of explosive economic growth and dynamic cities are front-loaded in the cycle of hegemonies and cities generating the myriad networks that produce hegemony. Whereas hegemony is not exercised by a single country, creative city networks are initially concentrated within one single state. Thus, prosperous cities are, to some extent, symbols of transformation of the systematic structure.[12]

There are also historical evidences listed by numerous professionals. Joel Kotkin notes that any successful city must have three characteristics of “sacredness, security, and economy.”[13] Fernand Braudel indicates that the city-centered world economy has been allowed to better integrate into their regional economies by the economic and trade networks of cities such as Venice, Antwerp, and Amsterdam.[14] Jacques Attali notes that the history of European economic growth has always been led by its strongest cities.[15] King and other relevant scholars apply Wallenstein’s dependence theory to explore how the world urban system can be viewed as a replication of the world system,[16] and point out that historical city trade networks illuminated the market economy by absorbing economic resources that had become “disembedded” from society.[17] Arrighi uses Marxism to explain that Genoa, Amsterdam, London, New York and other leading cities actually represent the capitalist cycle of accumulation and hegemony.[18] Historically, there indeed existed a strong correlation between rising world cities and the rise of their respective countries.

If rising world cities or cities initially with prosperous economy can influence and to some extent change the systematic structure, the way to promote the transformation of international institutions is through city diplomacy. Liberal internationalists insist that the international system could be stable mainly due to international institutions which combine different, even conflicting, interests of diverse actors at all levels. They describe that this is owed to all kinds of formal and informal international regimes. However, multilateralism at the national level is not always effective, encountering “democracy deficit,” “lack of driving forces,” “low efficiency,” and “unclear outcome,” thus the support from other various types of actors become necessary. Cities may use local-central channels to express ideas to the national authorities, draw insights from the underlying civil society, outwardly participate in international affairs, and incorporate those ideas into local policy and practice. Thus, cities have the potential to be the leaders, promoters and practitioners of multilateralism on a very special level. Like nations, cities have policy instruments to promote multilateralism, such as sister cities, inter-cities organizations, norm initiatives (e.g., Information Dissemination, Consulting, and Mass Communication Campaign), effective move on their own or form willing coalitions, etc. Such instruments fall under the category of city diplomacy. City diplomacy can be defined as “the institution and process by which cities or local governments in general, engage in relations with actors on an international political stage with the aim of representing themselves and their interests to one another,” and has various dimensions including security, development, economic, and culture. [19]