- WHAT IF CLINTON WINS ——US President...

- ‘Belt and Road’ initiative must wor...

- China’s Foreign Policy under Presid...

- China’s Foreign Policy under Presid...

- Criticism of CPEC is proof of progr...

- The Contexts of and Roads towards t...

- Seeking for the International Relat...

- Seeking for the International Relat...

- PRESIDENT BUHARI’S BALANCING ACT BE...

- Beyond the Strategic Deterrence Nar...

- The Belt and Road Initiative and Th...

- Wuhan 2.0: a Chinese assessment

- The Establishment of the Informal M...

- Identifying and Addressing Major Is...

- China’s Economic Initiatives in th...

- Perspective from China’s Internatio...

- Four Impacts from the China-Nordic ...

- Commentary on The U. S. Arctic Coun...

- Opportunities and Challenges of Joi...

- “Polar Silk Road”and China-Nordic C...

- BRI in Oman as an example: The Syn...

- The US Initiatives in Response to C...

- China-U.S. Collaboration --Four cas...

- Competition without Catastrophe : A...

- Lies and Truth About Data Security—...

- Addressing the Vaccine Gap: Goal-ba...

- The G20’s Sovereign Debt Agenda:Wha...

- Addressing the Vaccine Gap: Goal-ba...

- Leading the Global Race to Zero Emi...

- Health Silk Road 2020:A Bridge to t...

The Beijing Summit of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) scheduled for September will be the third summit of the forum since its inception in 2000. It will mark the first time that two FOCAC summits are held consecutively, following the Johannesburg Summit in 2015. Even before its opening, the Beijing Summit has drawn global attention and in particular, inspired African countries.

Expectations for FOCAC, to a large extent, stem from three major factors.

The foremost factor, which is also most frequently cited, is that FOCAC has driven the rapid development of China-Africa relations since its inception. Over the past 18 years, the annual trade volume between China and Africa multiplied 17 times, from US$10 billion in 2000 to US$170 billion in 2017, while China’s investment in Africa rose to US$40 billion from almost nothing. Alongside such directly visible achievements, China-Africa cooperation has also created significant and far-reaching strategic and theoretical results.

September 6, 1963: Chairman Mao Zedong meets with members of the visiting Kenya African National Union (KANU) delegation. by Liu Qingrui/Xinhua

December 19, 1967: Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai meets a delegation from the Tanganyika African National Union from Tanzania. by Liu Jianguo/Xinhua

To a large extent, FOCAC can promote rapid development of China-Africa cooperation because of its stability and predictability—the most important assets in a world full of uncertainties. Of all cooperation mechanisms related to Africa globally, FOCAC is one of only a few to operate on schedule for nearly 20 years. For instance, the EU-Africa Summit, launched in 2000, didn’t convene its second meeting until 2007 and missed one in-between. The latest Korea-Africa Forum, which was planned for May 2014, was postponed more than two years to December 2016. The latest India-Africa Forum Summit and Turkey-Africa Economic and Business Forum were both delayed more than a year. Despite the multiple cooperation mechanisms between the United States and Africa, the U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit was only held once in 2014. Since its inception in 2000, FOCAC has been held once every three years in addition to relevant meetings of foreign ministers and other high-ranking officials and coordination conferences on action plans implementation. FOCAC’s high-degree stability and predictability have provided a sound strategic and policy environment for cooperation.

1969: A Chinese medical team provides medical services for local herders in the Sahara in Algeria. Since China dispatched its first medical aid team to Africa in 1963, Chinese medical aid workers have treated millions of patients and trained tens of thousands of medical workers in over 50 African countries and regions. Xinhua

September 18, 1974: Then-Zambian President Kenneth Kaunda and other officials inspect the Chambishi River Bridge of the Tanzania-Zambia Railway. The 1,860-kilometer-long Tanzania-Zambia Railway was one of the major projects aided by China in Africa during the 1970s. Xinhua

The second factor driving FOCAC’s success is that China provides an alternative option for African countries to solve their practical problems. In the first half of the 20th century, China’s national liberation movement set an example for the national independence of African countries. For this reason, founding leaders of the People’s Republic of China such as Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai established profound and intimate friendships with African leaders like Kwame Nkrumah, Kenneth Kaunda and Julius Nyerere. Such historical connections laid a solid cornerstone for contemporary China-Africa cooperation. As a rule, more interactions trigger more frictions. However, it is such emotional connection that puts the brakes on the negative factors of China-Africa cooperation and prevents frictions from escalating. Statistics released by the Pew Research Center show that most African countries’ favorability towards China remained above 60 percent throughout the entire decade from 2007 to 2017.

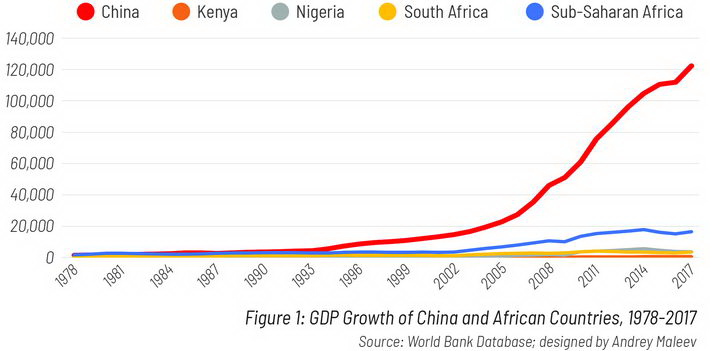

Today, China has set a new example for Africa with its development experience and achievements; a “great reversal” has been happening between China and Africa since the adoption of the reforming and opening-up policy. In 1978, China’s nominal GDP was about US$149.5 billion, and that of Sub-Saharan Africa was US$180.6 billion, including US$46.7 billion of South Africa, US$36.5 billion of Nigeria and US$5.3 billion of Kenya. China’s GDP had multiplied 81 times since to reach US$12 trillion by the end of 2017, much more than that of the entire African continent, let alone any single African country.

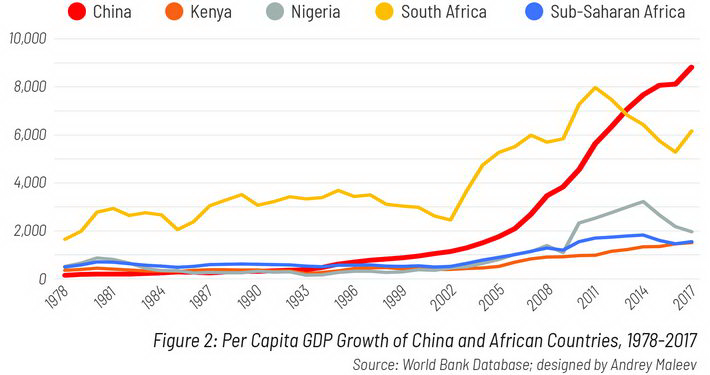

The same happened in terms of per capita GDP. In 1978, China’s per capita GDP was only US$156.4, much lower than US$1,651.6 of South Africa, US$527.1 of Nigeria and US$351.6 of Kenya. The Chinese figure was less than one-third of the average of Sub-Saharan Africa (which stayed at US$495.4). But now, China has overtaken all African countries, with its per capita GDP increasing to US$8,827 by the end of 2017, while the figure is US$6,160.7 in South Africa, US$1,968.6 in Nigeria, US$1,507.8 in Kenya, and US$1,553.8 on average in Sub-Saharan Africa.

This change verified the report to the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China: As socialism with Chinese characteristics has entered a new era, China is blazing a “new trail for other developing countries to achieve modernization” and offers a “new option for other countries and nations who want to speed up their development while preserving their independence.”

The third major factor driving FOCAC is that Africa is a top priority of China’s diplomacy and has become strategically important for China. From the perspective of China-Africa relations, China’s diplomacy has roughly undergone three stages in which Africa’s role evolved in ties between China and other parts of the world. Africa occupied a core position in the first stage and is playing a key role in the current third stage. The first stage extended from the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 until the adoption of the reform and opening-up policy in the late 1970s. During the period, the Cold War set the main tone of the world order, and China chose to stand on the side of the socialist camp headed by the Soviet Union, adopting a diplomatic policy of “cleaning up the house before inviting guests” (meaning it needed to clear out the remnants of imperialist forces in the country to pave the way for building equal diplomatic relations with countries around the world). After Sino-Soviet relations soured, Africa became the top priority for China’s diplomacy. The second stage started from the late 1970s and lasted until 2000, during which China placed priority on its relations with developed countries, in a bid to achieve a “rise through imitating” under the framework of international system. As China’s development entered a higher level, imitating developed economies could not solve emerging challenges to realize sustainable development. Meanwhile, developed countries became highly skeptical of China’s “rise through innovation” under the framework of international system. In this context, China’s diplomacy entered the third stage, during which the strategic importance of developing countries rebounded. At the 2018 central conference on diplomatic work, Chinese President Xi Jinping stressed that developing countries are China’s natural partners in international affairs and that China should take the moral high ground by working to benefit and promote solidarity and cooperation among developing countries. Undoubtedly, Africa ranks first among China’s “sincere partners and reliable friends.” It is needless to say that Africa and FOCAC are of great importance to China’s diplomacy.

December 10, 2014: Chinese doctors teach local medical workers infusion techniques at the China-Sierra Leone Friendship Hospital in Freetown, capital of Sierra Leone. by Dai Xin/Xinhua

July 24, 2018: Ma Xu, a railway worker from China Railway Jinan Group, instructs a Kenyan student on installing bolts. by Zhu Zheng/Xinhua

These three factors have not only guaranteed the successful operation of FOCAC over the past 18 years, but also laid a solid foundation for its future sustainable development. As China’s development enters a new era, China-Africa cooperation is also reaching a higher level. The key to China-Africa cooperation in this new era is to seize on the three factors fueling FOCAC. We must earnestly provide a new option for Africa while deeply understanding Africa’s strategic importance to China.

Source of documents:China Pictorial, Aug 31