- China’s Foreign Policy under Presid...

- The Contexts of and Roads towards t...

- Seeking for the International Relat...

- Three Features in China’s Diplomati...

- Smart gap widening

- Indian economy looks increasingly b...

- Reflecting on and Redefining of Mul...

- The Green Ladder & the Energy Leade...

- The Green Ladder & the Energy Leade...

- China-Sri Lanka Cooperation during ...

- The Establishment of the Informal M...

- China’s Economic Initiatives in th...

- Perspective from China’s Internatio...

- Commentary on The U. S. Arctic Coun...

- “Polar Silk Road”and China-Nordic C...

- Opportunities and Challenges of Joi...

- Opportunities and Challenges of Joi...

- Strategic Stability in Cyberspace: ...

- Promoting Peace Through Sustainable...

- Overview of the 2016 Chinese G20 Pr...

- Leading the Global Race to Zero Emi...

- Leading the Global Race to Zero Emi...

- Addressing the Vaccine Gap: Goal-ba...

- The Tragedy of Missed Opportunities

- Working Together with One Heart: P...

- China's growing engagement with the...

- Perspectives on the Global Economic...

- International Cooperation for the C...

- The EU and Huawei 5G technology aga...

- THE ASIAN RESEARCH NETWORK: SURVEY ...

Jan 01 0001

A Strong Voice for Global Sustainable Development: How China can Play a Leading Role in the Post-2015 Agenda

By

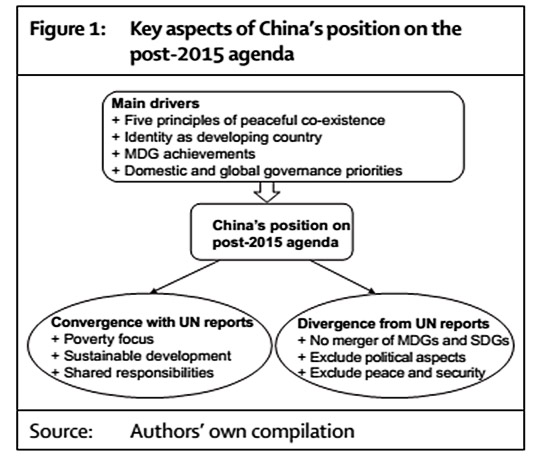

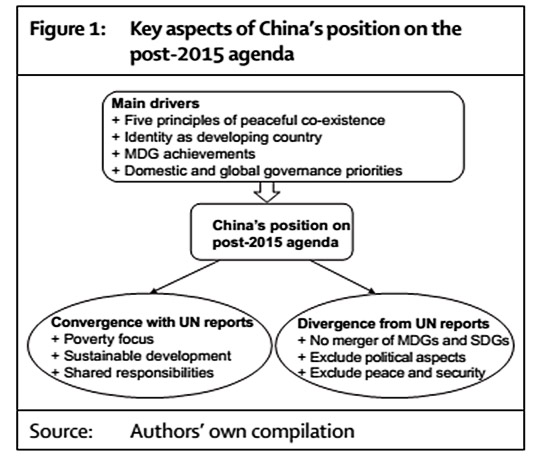

To the surprise of many, China has taken a pro-active stance in negotiations on the post-2015 agenda for global development at the United Nations (UN). In September 2013, the government issued a comprehensive position paper that aptly addresses a wide range of global challenges, from poverty eradication, inclusive growth and ecological conservation to international trade and the reform of global economic governance. The statement also impresses with a candid assessment of domestic advances and deficiencies, for example, income disparities and environmental degradation.

China’s position converges with major UN reports in key aspects, such as the overriding concern for poverty eradication and sustainable development. The paper diverges from these documents by rejecting the integration of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and by excluding political factors such as good governance and human rights.

The position paper of September 2013 may not be China’s final word on the post-2015 agenda. Shortly after its publication, the country demonstrated considerable flexibility by agreeing to a resolution of the UN General Assembly which emphasises the need for a single set of goals and underlines the significance of political framework conditions for development – positions which China had previously rejected.

China’s early intervention represents an exemplary case of articulating national priorities. The country should now move to the second stage of pro-active policy formulation by specifying its contributions and ambitions. Recent statements of the communist party leadership signal a heightened interest in global governance. The ongoing negotiations on post-2015 offer a historical opportunity for China to demonstrate its commitment by increasing material support for South-South development cooperation and the provision of global public goods. The government should support the integration of MDGs and SDGs and open up to the concerns of fragile and conflict affected countries, as articulated by the African Union and the interstate alliance G7 .

Also, China should use its influence in the global South to work for an ambitious post-2015 agenda, thus breaking the persistent gridlock in international affairs. In parallel, the country’s leadership should accelerate domestic transformation towards a low-carbon, resource-light model of prosperity and overcome social disparities. Propelled by theses priorities, China’s leadership could significantly enhance the country’s soft power and international reputation. Acting as a bridge between the G77 and industrial countries, China could strengthen the authority of the United Nations as the legitimate guardian of global well-being. Advanced countries like Germany should follow the Chinese example by providing a comprehensive plan of action for international and domestic policies aligned to the post-2015 agenda.

Key points of China’s position paper

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China issued its “Position Paper on the Development Agenda beyond 2015” in September 2013, shortly before the special event of the United Nations which reviewed progress on the MDGs. A comparison of the Chinese document with key UN reports reveals convergence, but also divergence on critical issues.

China and four important UN bodies (the UN System Task Team; the High-Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda; the Open Working Group of the General Assembly on Sustainable Development Goals; and the Sustainable Development Solutions Network) concur on the following points: Poverty eradication is a core element of the post-2015 agenda. Sustainable development and inclusive growth are prerequisites for prosperity and social welfare. All countries share responsibilities in addressing global challenges according to their capabilities. Finally, South-South cooperation is a useful supplement to North-South cooperation, but traditional donors must not renege on their commitments.

Chinese views are also close to policy statements of the European Commission and the European Report on Development 2013, prepared by a think tank consortium. This proves that there has been a considerable degree of convergence between China and the international community on the design of the post-2015 agenda.

However, disagreement between China on the one side and UN and European voices on the other prevails with regard to the following aspects: China is not in favour of replacing MDGs by SDGs and even has reservations about the merger of the two concepts. The country is opposed to the inclusion of political factors like human rights, democracy and good governance and does not support linking peace and security issues to the post-2015 framework.

Underlying principles of China’s views

The position paper makes the case that four underlying principles should shape the post-2015 agenda. They represent core elements of China’s foreign policy with regard to non-interference and equitable burden-sharing. They also reflect the strategic objective of consolidating China’s alliance with developing countries (G77) by emphasising the primacy of growth and development.

1. Respect sovereignty and diversity in development models: The post-2015 agenda should serve as a guide and frame of reference for national development strategies, not as a tool for interfering in internal affairs. Although peace and security clearly are a prerequisite to development, the Chinese government is convinced that such topics should be excluded from the new agenda, because this would detract from genuine development goals and violate the sovereignty principle.

2. Manage international burden-sharing: The principle of“common but differentiated responsibilities” (CBDR)which was formally established in 1992 at the Rio Earth Summit is a manifestation of equity in international law. In fact, the principle can be traced back to the early 1970s when the UN General Assembly established a target for industrial countries to contribute 0.7 % of their national income as assistance to developing countries. However, the position paper falls short of spelling out how CBDR could be made operational in the context of post-2015. Nor does it provide specific information on China’s future transfers to low-income countries or to the provision of global public goods.

3. Build on the MDGs:Although the 2000 Millennium Declaration which serves as legitimation of the MDGs stresses the close relationship between development and political factors like human rights, democracy, good governance and rule of law, the MDGs as such do not include these elements due to insurmountable dissent among UN member states. In continuation of the MDG tradition, China wants the post-2015 framework to refrain from incorporating contested political targets.

4. Avoid an overloaded agenda:China’s position paper does not explicitly refer to SDGs which the General Assembly wants to adopt in 2015, based on a decision at the 2012 Rio 20 Summit in Brazil. This signals an objection to the integration of MDGs and SDGs. The lack of support for a common framework of MDGs and SDGs may be of diplomatic, not principled nature owing to sensibilities of developing countries, since the Chinese text pays considerable attention to the promotion of economic, social and environmental development in a balanced way.

Driving forces of China’s policies

China’s position in the post-2015 process is shaped by a variety of normative factors and practical considerations. To better understand China’s role in intergovernmental negotiations on post-2015, it is useful to examine the drivers which determine the country’s foreign policy as well as the transformation of its economy and society.

Five principles of peaceful co-existence

The five principles of peaceful co-existence – mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity; mutual non-aggression; non-interference in each other’s internal affairs; equality and mutual benefit; and peaceful coexistence – are the fundamental normative framework for China in international affairs. They were proposed by former Premier Zhou Enlai in 1953 and to this day guide the country’s foreign policy. The principles have been accepted by most countries in the world, especially by developing countries, and have become an important norm of international relations.

China considers its participation in the setting of the post-2015 development agenda as an important diplomatic action. The fact that China's position paper was issued by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is evidence of this. It is, therefore, only natural for China to acknowledge the five principles of peaceful coexistence by emphasising the autonomy of all countries in pursuing their own national development strategies and targets.

However, China’s expanding links with the developing world may soon lead to a critical examination of strict non-interference since political instability and violent conflicts in partner countries not only erode the foundations for domestic prosperitybut also threaten the economic interests and personal safety of foreign actors. In shaping its future foreign policy, China should therefore pay increased attention to the internal conditions of developing countries and consider appropriate ways of fostering stability and crisis prevention.

China’s identity as developing country

China’s government insists on its international status as largest developing country although its economy ranks number two in the world. The communist party openly admits that the country struggles with meeting the evergrowing material and cultural needs of the population. In 2009, more than 100 million people still lived in extreme poverty. Measured by 2012 per capita income, China ranks 93 in international comparison.

The identity of China as a developing country is one of the reasons why the position paper emphasises poverty eradication and development as core of the new framework. However, as China’s prosperity and international weight continue to grow, its rising capabilities and power resources call for a reconsideration of identity. The country should prepare for the moment when the world no longer shares the view of China as a developing country, but rather expects an international performance commensurate to its status as a global leader. And it should define its objectives and streamline its practices as the most important provider of SouthSouth development cooperation, for example in regard to transparency and accountability.

Achievements in implementing the MDGs

The country’s focus on poverty eradication is shaped by its successful track record at home. Extreme poverty in China dropped from 60 per cent in 1990 to 16 per cent in 2005 and 12 per cent in 2010.Since 2003, the Chinese Foreign Ministry, working together with the UN system, released a total of five reports on “Progress in China’s Implementation of the Millennium Development Goals” which demonstrate the country’s achievements. The latest report states that in 2013, two years ahead of the finishing line, China had achieved nearly half of the MDGs. However, the impressive progress may be more a result of domestic priorities independent of global goals.

Promoting domestic and global governance

In November 2013, the third plenary session of the eighteenth central committee of the communist party initiated a novel discourse about transforming the traditional top-down style of state rule into a new mode of interactive, multi-stakeholder governance. This signals long-term changes in China’s development philosophy. The meaning of social progress will no longer be confined to economic growth and material improvement but framed by a holistic concept of multi-dimensional sustainable development.

Parallel to internal changes, China’s leadership is determined to strengthen international efforts because the boundaries between domestic and world affairs are becoming blurred and the country has become an important actor at the centre of the global system.

From a series of documents approved at recent meetings of the communist party, we can see that the promotion of national governance and participation in global governance have become dominant trends in China’s policies. It is, therefore, logical that China will pay more attention to environmental protection, climate change and other issues of sustainable development related to global challenges.

Outlook

As China becomes more influential on the world stage and plays a more important role in the field of international development cooperation, the international community needs to pay more attention to differences of opinion with China and try to find ways to address them in a constructive way. Similarly, China needs to listen to the concerns of others. China should use its enormous influence in the global South (e.g. G77 and BRICS) but also in the G20 to promote a consensus of developing and industrial countries on cooperative responses to global challenges.

The fact that China agreed to a landmark resolution of the UN General Assembly on post-2015 shortly after the publication of its position paper demonstrates a high degree of flexibility since member states spoke out in favour of merging MDGs and SDGs and wanted to include political factors. Future negotiations will show to what extent China will modify its positions to facilitate a meaningful universal consensus and what commitments the country will undertake at home and abroad to support the post-2015 agenda.

Policy recommendations

In order to demonstrate its heightened interests in global governance and to play a leading role in the post-2015 agenda for global development China’s leadership should consider the following recommendations:

– Support the integration of MDGs and SDGs into a single framework and set of goals.

– Strengthen the universal character of the post-2015 agenda by demonstrating how China will accelerate structural transformation of its economy, aligned to the requirements of planetary sustainability.

– Lift the remaining 120 million people from extreme poverty in China in the next 15 years.

– Issue a concrete statement on the expansion of assistance to developing countries over the next decades. The average quota of OECD countries’ ODA to GNI should be the point of reference for China and other rising powers (official development assistance to gross national income).

– Support the position of fragile and conflict-affected countries, as articulated by the African Union and the interstate alliance G7 , on the inclusion of peace and security in post-2015, under the prerogative of the Security Council.

– Specify future contributions of China to the provision of key global public goods, like climate protection, economic stability, UN peace keeping, health etc.

– Assume political and intellectual leadership in the South, including the G77 and BRICS, to facilitate a global consensus on an ambitious post-2015 framework.

The position paper of September 2013 may not be China’s final word on the post-2015 agenda. Shortly after its publication, the country demonstrated considerable flexibility by agreeing to a resolution of the UN General Assembly which emphasises the need for a single set of goals and underlines the significance of political framework conditions for development – positions which China had previously rejected.

China’s early intervention represents an exemplary case of articulating national priorities. The country should now move to the second stage of pro-active policy formulation by specifying its contributions and ambitions. Recent statements of the communist party leadership signal a heightened interest in global governance. The ongoing negotiations on post-2015 offer a historical opportunity for China to demonstrate its commitment by increasing material support for South-South development cooperation and the provision of global public goods. The government should support the integration of MDGs and SDGs and open up to the concerns of fragile and conflict affected countries, as articulated by the African Union and the interstate alliance G7 .

Also, China should use its influence in the global South to work for an ambitious post-2015 agenda, thus breaking the persistent gridlock in international affairs. In parallel, the country’s leadership should accelerate domestic transformation towards a low-carbon, resource-light model of prosperity and overcome social disparities. Propelled by theses priorities, China’s leadership could significantly enhance the country’s soft power and international reputation. Acting as a bridge between the G77 and industrial countries, China could strengthen the authority of the United Nations as the legitimate guardian of global well-being. Advanced countries like Germany should follow the Chinese example by providing a comprehensive plan of action for international and domestic policies aligned to the post-2015 agenda.

Key points of China’s position paper

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China issued its “Position Paper on the Development Agenda beyond 2015” in September 2013, shortly before the special event of the United Nations which reviewed progress on the MDGs. A comparison of the Chinese document with key UN reports reveals convergence, but also divergence on critical issues.

China and four important UN bodies (the UN System Task Team; the High-Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda; the Open Working Group of the General Assembly on Sustainable Development Goals; and the Sustainable Development Solutions Network) concur on the following points: Poverty eradication is a core element of the post-2015 agenda. Sustainable development and inclusive growth are prerequisites for prosperity and social welfare. All countries share responsibilities in addressing global challenges according to their capabilities. Finally, South-South cooperation is a useful supplement to North-South cooperation, but traditional donors must not renege on their commitments.

Chinese views are also close to policy statements of the European Commission and the European Report on Development 2013, prepared by a think tank consortium. This proves that there has been a considerable degree of convergence between China and the international community on the design of the post-2015 agenda.

However, disagreement between China on the one side and UN and European voices on the other prevails with regard to the following aspects: China is not in favour of replacing MDGs by SDGs and even has reservations about the merger of the two concepts. The country is opposed to the inclusion of political factors like human rights, democracy and good governance and does not support linking peace and security issues to the post-2015 framework.

Underlying principles of China’s views

The position paper makes the case that four underlying principles should shape the post-2015 agenda. They represent core elements of China’s foreign policy with regard to non-interference and equitable burden-sharing. They also reflect the strategic objective of consolidating China’s alliance with developing countries (G77) by emphasising the primacy of growth and development.

1. Respect sovereignty and diversity in development models: The post-2015 agenda should serve as a guide and frame of reference for national development strategies, not as a tool for interfering in internal affairs. Although peace and security clearly are a prerequisite to development, the Chinese government is convinced that such topics should be excluded from the new agenda, because this would detract from genuine development goals and violate the sovereignty principle.

2. Manage international burden-sharing: The principle of“common but differentiated responsibilities” (CBDR)which was formally established in 1992 at the Rio Earth Summit is a manifestation of equity in international law. In fact, the principle can be traced back to the early 1970s when the UN General Assembly established a target for industrial countries to contribute 0.7 % of their national income as assistance to developing countries. However, the position paper falls short of spelling out how CBDR could be made operational in the context of post-2015. Nor does it provide specific information on China’s future transfers to low-income countries or to the provision of global public goods.

3. Build on the MDGs:Although the 2000 Millennium Declaration which serves as legitimation of the MDGs stresses the close relationship between development and political factors like human rights, democracy, good governance and rule of law, the MDGs as such do not include these elements due to insurmountable dissent among UN member states. In continuation of the MDG tradition, China wants the post-2015 framework to refrain from incorporating contested political targets.

4. Avoid an overloaded agenda:China’s position paper does not explicitly refer to SDGs which the General Assembly wants to adopt in 2015, based on a decision at the 2012 Rio 20 Summit in Brazil. This signals an objection to the integration of MDGs and SDGs. The lack of support for a common framework of MDGs and SDGs may be of diplomatic, not principled nature owing to sensibilities of developing countries, since the Chinese text pays considerable attention to the promotion of economic, social and environmental development in a balanced way.

Driving forces of China’s policies

China’s position in the post-2015 process is shaped by a variety of normative factors and practical considerations. To better understand China’s role in intergovernmental negotiations on post-2015, it is useful to examine the drivers which determine the country’s foreign policy as well as the transformation of its economy and society.

Five principles of peaceful co-existence

The five principles of peaceful co-existence – mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity; mutual non-aggression; non-interference in each other’s internal affairs; equality and mutual benefit; and peaceful coexistence – are the fundamental normative framework for China in international affairs. They were proposed by former Premier Zhou Enlai in 1953 and to this day guide the country’s foreign policy. The principles have been accepted by most countries in the world, especially by developing countries, and have become an important norm of international relations.

China considers its participation in the setting of the post-2015 development agenda as an important diplomatic action. The fact that China's position paper was issued by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is evidence of this. It is, therefore, only natural for China to acknowledge the five principles of peaceful coexistence by emphasising the autonomy of all countries in pursuing their own national development strategies and targets.

However, China’s expanding links with the developing world may soon lead to a critical examination of strict non-interference since political instability and violent conflicts in partner countries not only erode the foundations for domestic prosperitybut also threaten the economic interests and personal safety of foreign actors. In shaping its future foreign policy, China should therefore pay increased attention to the internal conditions of developing countries and consider appropriate ways of fostering stability and crisis prevention.

China’s identity as developing country

China’s government insists on its international status as largest developing country although its economy ranks number two in the world. The communist party openly admits that the country struggles with meeting the evergrowing material and cultural needs of the population. In 2009, more than 100 million people still lived in extreme poverty. Measured by 2012 per capita income, China ranks 93 in international comparison.

The identity of China as a developing country is one of the reasons why the position paper emphasises poverty eradication and development as core of the new framework. However, as China’s prosperity and international weight continue to grow, its rising capabilities and power resources call for a reconsideration of identity. The country should prepare for the moment when the world no longer shares the view of China as a developing country, but rather expects an international performance commensurate to its status as a global leader. And it should define its objectives and streamline its practices as the most important provider of SouthSouth development cooperation, for example in regard to transparency and accountability.

Achievements in implementing the MDGs

The country’s focus on poverty eradication is shaped by its successful track record at home. Extreme poverty in China dropped from 60 per cent in 1990 to 16 per cent in 2005 and 12 per cent in 2010.Since 2003, the Chinese Foreign Ministry, working together with the UN system, released a total of five reports on “Progress in China’s Implementation of the Millennium Development Goals” which demonstrate the country’s achievements. The latest report states that in 2013, two years ahead of the finishing line, China had achieved nearly half of the MDGs. However, the impressive progress may be more a result of domestic priorities independent of global goals.

Promoting domestic and global governance

In November 2013, the third plenary session of the eighteenth central committee of the communist party initiated a novel discourse about transforming the traditional top-down style of state rule into a new mode of interactive, multi-stakeholder governance. This signals long-term changes in China’s development philosophy. The meaning of social progress will no longer be confined to economic growth and material improvement but framed by a holistic concept of multi-dimensional sustainable development.

Parallel to internal changes, China’s leadership is determined to strengthen international efforts because the boundaries between domestic and world affairs are becoming blurred and the country has become an important actor at the centre of the global system.

From a series of documents approved at recent meetings of the communist party, we can see that the promotion of national governance and participation in global governance have become dominant trends in China’s policies. It is, therefore, logical that China will pay more attention to environmental protection, climate change and other issues of sustainable development related to global challenges.

Outlook

As China becomes more influential on the world stage and plays a more important role in the field of international development cooperation, the international community needs to pay more attention to differences of opinion with China and try to find ways to address them in a constructive way. Similarly, China needs to listen to the concerns of others. China should use its enormous influence in the global South (e.g. G77 and BRICS) but also in the G20 to promote a consensus of developing and industrial countries on cooperative responses to global challenges.

The fact that China agreed to a landmark resolution of the UN General Assembly on post-2015 shortly after the publication of its position paper demonstrates a high degree of flexibility since member states spoke out in favour of merging MDGs and SDGs and wanted to include political factors. Future negotiations will show to what extent China will modify its positions to facilitate a meaningful universal consensus and what commitments the country will undertake at home and abroad to support the post-2015 agenda.

Policy recommendations

In order to demonstrate its heightened interests in global governance and to play a leading role in the post-2015 agenda for global development China’s leadership should consider the following recommendations:

– Support the integration of MDGs and SDGs into a single framework and set of goals.

– Strengthen the universal character of the post-2015 agenda by demonstrating how China will accelerate structural transformation of its economy, aligned to the requirements of planetary sustainability.

– Lift the remaining 120 million people from extreme poverty in China in the next 15 years.

– Issue a concrete statement on the expansion of assistance to developing countries over the next decades. The average quota of OECD countries’ ODA to GNI should be the point of reference for China and other rising powers (official development assistance to gross national income).

– Support the position of fragile and conflict-affected countries, as articulated by the African Union and the interstate alliance G7 , on the inclusion of peace and security in post-2015, under the prerogative of the Security Council.

– Specify future contributions of China to the provision of key global public goods, like climate protection, economic stability, UN peace keeping, health etc.

– Assume political and intellectual leadership in the South, including the G77 and BRICS, to facilitate a global consensus on an ambitious post-2015 framework.

Source of documents:German Development Institute

more details: